How did a massive study that launched during COVID manage to continue work to tackle the overdose crisis? SIG interviewed two on-the-ground organizers of the HEALing Communities Study in Ulster County, one of the participating counties. Also, a remembrance of Adam C. Nadiak.

Introduction and interview of Juanita Hotchkiss and Jillian Nadiak by Eleni Vlachos

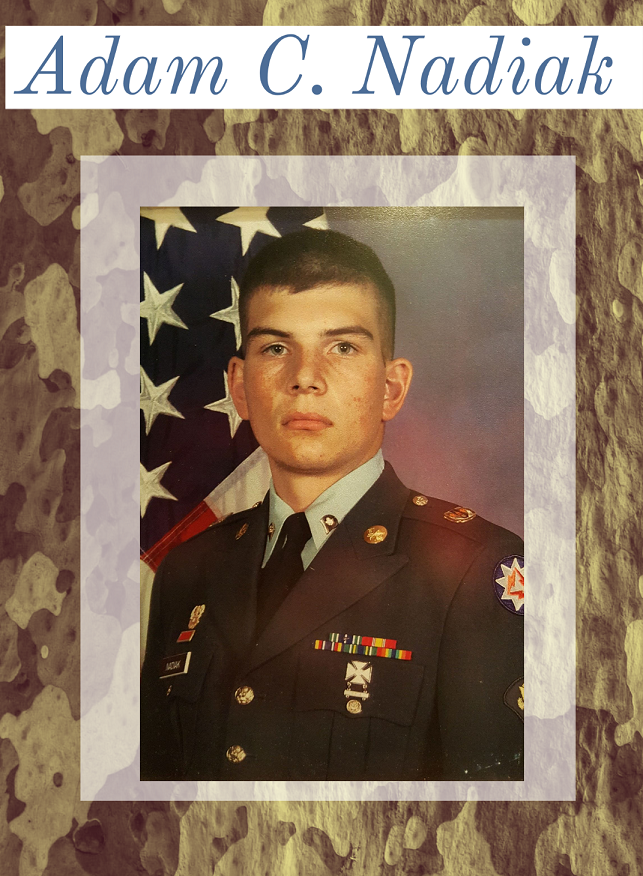

Adam C. Nadiak was eager to enlist in the US Army right after high school. When Adam enlisted, his grandfather, a World War II veteran and Adam’s hero, was tentative about this choice. His grandfather had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from his own experiences and might have worried that his grandson may also have to live with similar demons. Perhaps he even feared his grandson would die in Afghanistan. Little did he know that it was not the war -- directly -- that would take his grandson from the world. It was something much more insidious.

Adam excelled during his service, even winning the Soldier of the Year award. Following his service, Adam returned to his family, and later worked as an information technology analyst for security and disaster recovery. For years following, he suffered back pain due to an injury sustained in the military, as well as anxiety and PTSD. He began taking a prescription painkiller which eased the pain and muted -- somewhat -- his PTSD. Soon, however, the prescribed medicine was no longer sufficient, and he became addicted to the medication.

As is common among vets, who are trained to embody strength, Adam had difficulty in telling even the closest among him about his suffering. It was only later that his family found several letters expressing feelings of unworthiness and suicidal thoughts.

Then, on a beautiful April day in 2016, ten years following the end of his service, his family received a devastating call: Adam died in his new apartment of an opioid overdose.

Adam’s case has become all too familiar. More people in the US die from overdose than from automobile accidents. The numbers were, and continue to be, staggering. Over the past year, hundreds of community leaders, doctors, scientists, government leaders, academics, and organizations mobilized to address this crisis in New York State.

Then, Covid-19 hit. On March 20th, New York (officially) shut down.

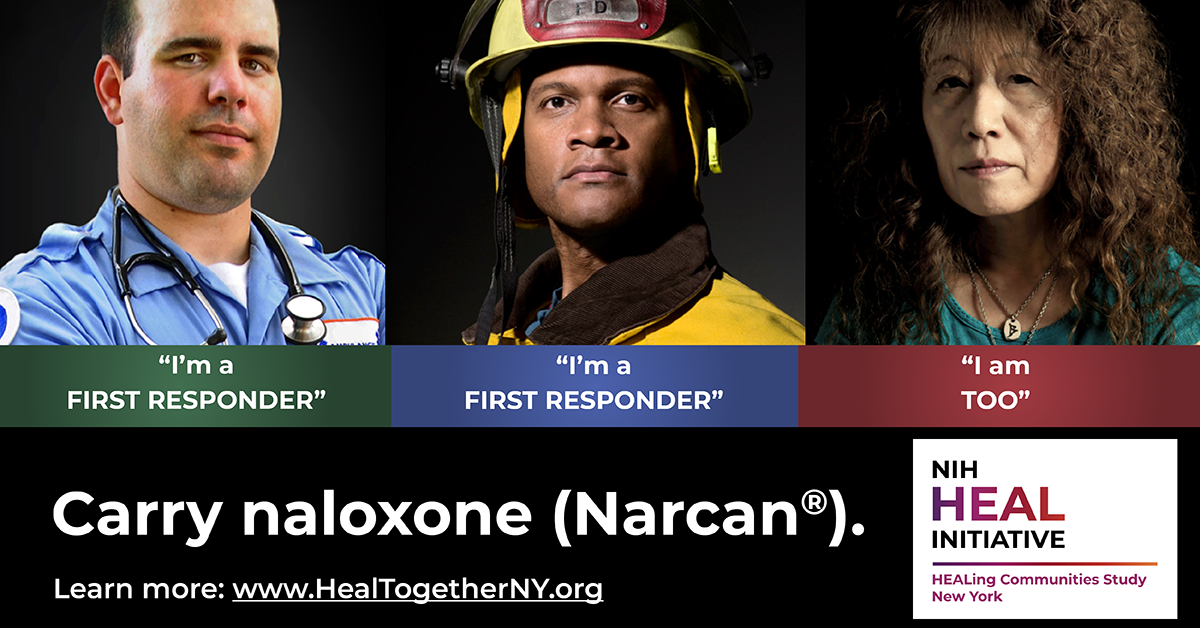

Amid the restrictions and shutdowns, a group of people who had assembled to address the overdose crisis -- members of the newly launched HEALing Communities Study -- had to quickly calculate how they could keep operating to address the overdose epidemic while keeping everyone as safe as possible. They were launching their first campaign to fastrack Narcan, a life-saving drug to reverse overdoses. How would they be able to distribute the lifesaving Narcan to the people who needed it most? Certainly not via Zoom.

Recently, SIG's Eleni Vlachos spoke with two key organizers who work directly on this question with HEALing and their communities for Ulster County: Juanita Hotchkiss, the Project Manager, and Jillian Nadiak, the Community Engagement Facilitator and Technical Assistance Specialist.

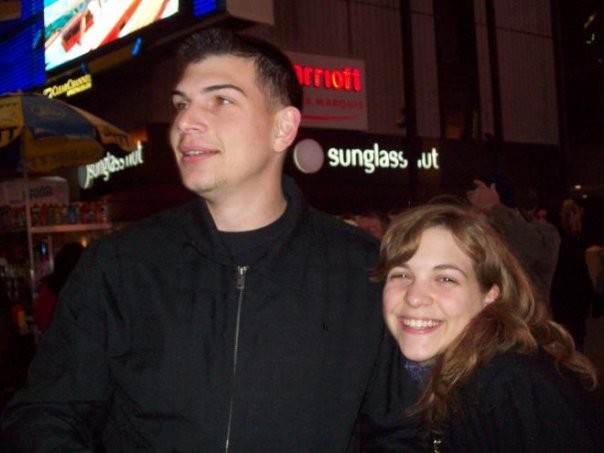

Jillian also has a personal reason for getting involved: Adam C. Nadiak is her brother.

Juanita and Jillian are at the forefront of the work to address the overdose crisis within the HEALing Communities Study, working on the ground directly with impacted communities. Both women work for Ulster County, one of the eight counties in the first wave of the Study.

SIG was fortunate to hear from them both and learn how they are quickly shifting their strategies to ensure that the needs of impacted individuals can still be met.

At the time of the interview, HCS’s aforementioned first campaign to “fast-track” Narcan was well underway. Narcan, or naloxone, is an important tool in the overdose crisis because, simply put, it saves lives.

Introducing Juanita Hotchkiss

Juanita began with Ulster County and the HEALing Communities Study (HCS) this past March. She helps transform hundreds of pages of research protocol into actual practice. Juanita convenes the Community Coalition, which is comprised of a diverse group of people and professions. The Coalition includes those with lived experience with substance use, community organizations, professionals in healthcare, the criminal justice system, treatment programs, government agencies, and more.

What drew you to the HEALing Communities Study (HCS)?

Our community was hit significantly hard. Ι lost a close friend to heroin a few years ago. No six degrees of separation. Ι feel compelled to be part of a solution, and coalition work -- community building and capacity building -- is tried and true. It calls me. I have a passion from both personal experience and for my community. HCS felt like the place to merge both. The scale of HCS is huge. I’ve been doing different forms of coalition work for five to six years, and worked on other higher education projects. I felt like this particular position encompassed it all.

What is it like working for HCS in Ulster County?

It’s exciting! When you’re doing coalition work you’re working to build community capacity from the top down, and bottom up. I feel a tremendous surge of support from leadership, trickling downward. Ulster county is filled with grass roots organizations; agencies that see a need and meet the need. I see my role with HCS as a collaborative partner with community members, the agencies that serve them, and county government.

Ulster is also involved in a multi county collaborative which includes counties such as Putnam, Orange, Columbia, and Greene. The opioid epidemic doesn't see county lines or borders. Developing relationships and networks beyond our communities is so important to achieving our ultimate goal. The HCS not only supports these connections but encourages them.

Tell me about the Ulster coalition.

Ulster has a huge task force which began a few years ago. I was working for a university at the time and the County leadership contacted me to see if I would help facilitate the prevention arm of the strategic planning team. The coalition began with close to 60 members, and we’ve had those same solid members through the entire process. When HCS came in, we merged our existing task force with HCS and transitioned to the Ulster County strategic action team. We have close to 50 members who attend our monthly meetings regularly. Members include the business sector, behavioral health, criminal justice, first responders, those with lived experience, grassroots community organizations, hospitals, and leadership in those sectors. We also have smaller work groups that meet twice per month. We are so fortunate to have such a huge amount of community support for the work that we are doing.

How did the Coalition and work groups adapt to COVID?

When COVID hit people had to figure out how to do this work in an adaptable way. We had to prioritize our approach: How can we fast track these strategies? We were all used to interacting face to face.

First, with technical assistance from HCS, I developed a presentation outlining many possible options for the virtual training, and presented it to the work group. Agencies adapted the ideas to meet their own style and needs. In collaboration with many partners our group ended up launching six virtual Narcan trainings serving hundreds of folks in Ulster and regionally. We partnered with other regions and communities to reach as many people as we could. This partnership also created a distribution network.

Who attends Narcan training sessions?

Training participants come from all over our county and beyond. Our workgroup also put together a provider panel to attend each Virtual training and help answer questions and provide information on services.

Our work group developed a system to see where people are, and what areas of our country are being met and not being met. Feedback through surveys also helps inform our approach. We have heard that the virtual training is great and Coalition members want to continue this option post-COVID too. We created partnerships that maybe would not have existed otherwise.

What kind of information is shared in Narcan trainings?

Trainings include a demonstration video on how to safely use Narcan. The video also includes rescue breathing techniques, safely with COVID in mind, as well as safe administration of Narcan. Everyone who attends a training is offered information about harm reduction information, linkage to opioid use disorder services, and access to med disposal bags. The work group felt it was important to provide as many resources as possible to participants while we had them close.

At least nine people -- individuals at the highest risk -- have been revived using [the Narcan we distributed]."

Learn more about administering Narcan safely during COVID

How has COVID impacted your ability to bring together a coalition? How do you keep people in HCS engaged since they cannot go to meetings?

After COVID, we moved all meetings right to Zoom, and 45-plus people attend our two-hour meetings each month. We had growing pains but found a happy medium, and most of our members have been very receptive to this new format. The move online has encouraged and engaged folks in ways we had not been able to do before. Our region is large; attending a monthly coalition meeting and a work group meeting once every two weeks would not have been possible for most. For some, it would have meant an hour drive. Now, it’s more accessible. People from all over can come together quickly.

What are some examples you have seen of adaptations for COVID?

There has been an influx of telehealth and telemedicine with all of our agencies and larger primary care agencies. Everyone is embracing technology in that way. As long as regulations allow, their intent is to continue on. We are hearing that there has been an uptick in primary care visits, and people keeping their appointments in our County as a whole. We are also re-envisioning who can work from home: who needs to be at home and who needs to work from the office.

Our new virtual world can cause barriers though for those without the Internet or a phone.

How do counties address access for those without wifi?

It’s not easy. All schools in Kingston provide wifi hotspots in parking lots. We are currently examining how we can develop a sustainable way for individuals who do not have a phone or access to wifi to be able to use these online services and gain telehealth accessibly.

What have you found inspiring in this work and/or adaptations?

After the virtual Narcan training sessions, the work group started looking at impact areas not being reached by the training, or “hot spot” areas where there were increased overdoses. The aim was to come up with strategies to meet the needs of these areas.

Now, we have a new agency doing an on-site in person distribution on a regular basis, using social distancing and other measures. Due to their efforts, we learned that at least nine people -- individuals at the highest risk -- have been revived using those kits. These are the stories that are coming in from the agency who took the lead as members of our work group. Each week they go back, and we get more feedback. They are truly creating relationships. I am inspired by this.

What are the next steps for HEALing?

We will be addressing stigma and medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD). Stigma is important because it prevents people from getting help or speaking up. Stigma is a community issue. Addiction is a disease. The more that we talk about naloxone distribution and MOUD, we are destigmatizing drug addiction. We will also continue developing our action and implementation plan with the coalition. Our hope is that we will begin implementing the interventions near the end of the summer. I think we are all looking forward to seeing an impact. Our community is ready to heal.

I recommend you speak with Jillian Nadiak: She does great work and has a powerful story. (Done!)

Introducing Jillian Nadiak

Jillian began with Ulster County and the HEALing Communities Study (HCS) this past April. As the Community Engagement Coordinator and Technical assistance Specialist, she works directly with community work groups on important topics relating to addressing the overdose crisis. As shared in the story above, Jillian lost her brother Adam to an overdose in 2016. In addition to her role with HCS, she runs a scholarship for veterans in honor of her late brother.

What drew you to the HCS study?

I heard about the HEALing grant through the County Executive’s office. I lost my brother in 2016 to this, so it’s close to my heart. For the last four years I had been doing opioid prevention work in my free time. I feel lucky that this exists so I can now work on it every day but I hope I can work myself out of the job sooner than later, of course.

A year after my brother passed, I created the Adam C Nadiak Memorial Scholarship. I wanted to make it clear to the community who he was. I held my first event, a dinner in celebration of his life on the one year anniversary of his passing, and didn’t know what to expect and raised $3,000 in one night. The next was around his birthday, a concert in Kingston, New York. The Karate Academy I attended hosted a self-defense seminar. Angry Orchard donated $13,000. They choose an organization to donate their tips to a few times a year. My second year scholarship recipient worked there and advocated for Adam’s scholarship. I was shocked when he told me it was chosen. The funds go to a SUNY Ulster student who is pursuing a degree to help veterans. Veteran students are given extra consideration. We have had amazing recipients.

I wish the amazing work that we’re doing now was available when my brother was alive.

Tell me about your role with HCS and Ulster.

My main role is working with the work groups that break off from the coalition. Coalition members join different groups like safe dispensing, and I help facilitate their conversations. Members include people working in the field, which also includes people with lived experience. People start hammering out ideas with a lot of passion. For example, our safer prescribing work group decided it would be good to create an advisory board of providers and prescribers to pull together best practices and communicate this information to their peers.

Now that everything is on Zoom, people are more enticed to show up. Zoom has inspired virtual Narcan trainings. There were 250 people on a recent regional training.

What does the forthcoming stigma campaign mean to you?

I wish the amazing work that we’re doing now was available when my brother was alive, both medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and destigmatization strategies. I found out after he passed by finding old notebooks that he was trying to get better, setting his own tapering plans by counting how many he thought he would absolutely need to have in a month and getting rid of any extras. This is a dangerous game as sometimes you don’t know how many you will need by the end of the month when you are struggling with addiction and chronic pain and when you are left without, you will turn anywhere to get what you need. He thought he was doing a good thing. There is no shame in seeking help. No one should go through that process alone. I hope everyone knows that MOUD is available because to me, I think that would have been a resource that could have been helpful for someone like him.

Stigma is reduced by enough awareness and people speaking out. Everyone knows someone who has been impacted by the overdose epidemic, but many find it hard to speak out because of the stigma. It's a vicious cycle.

Even within our own family, it took my Mom a long time to acknowledge how my brother died: Of overdose, not cancer. I don't blame her for this. The year he died, 2016, wasn’t a long time ago. But even then, the idea of having lost someone to an overdose was a difficult thing to accept, both socially and personally for so many people. I had to accept it immediately, because it's what the doctor said when I was the first one to answer the phone that day. I didn’t have an option but to accept the truth. Even though we knew of his addiction for 10 years, an overdose was the last thing my Mom thought of happening. Given his young age, it only made sense he was hiding cancer from us.

Societal stigma enabled her to make this conclusion both because of the fear of what people would think (ourselves included) and the unfathomable idea that a medication could have taken over someone’s life the way it did. Eventually my mom and I had an honest conversation with each other. My mom and I no longer live in this stigma because we had to move beyond this to live a happy life after Adam’s loss, together. I don’t want others to have to take that same journey towards understanding. We have come a long way in just the last few years but there is still so much work to be done.

So many people perpetuate the idea that people addicted to drugs are underclass. People also tell me they had no idea that Adam was struggling with addiction. My brother, Soldier of the Year. If it can happen to him, it can happen to anyone.

The HEALing Communities Study is funded by NIH.

Stay tuned for the next campaign in the HEALing Communities Study, specifically targeting stigma and increasing awareness about the importance of medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD). The HCS team also convened a work group exploring structural racism and opioids, and is developing action plans with each of the first wave of counties.

-

Learn more about the HEALing Communities Study

-

Find resources in Ulster County

-

Read about the Adam C. Nadiak Memorial Scholarship

-

Follow SIG's work by signing up for our monthly newsletter or following us on Twitter